Regulatory Science and the Development of a COVID-19 Vaccine

MBP Assistant Director of Research Arthur Felse explains the regulatory approval process and why it's important not to rush any new preventative therapies.

In less than nine months, more than 60 million people worldwide have tested positive for COVID-19 and nearly 1.5 million people have died. The numbers are staggering in the United States, where there have been more than 15 million cases and more than 283,000 deaths.

As the world awaits an approved vaccine, many people wonder why the process is taking so long. Arthur Felse, the assistant director of research for Northwestern Engineering's Master of Biotechnology Program (MBP), recognizes the public's anxiousness for a preventative measure. He also understands that something like this takes time, and rushing through the testing and registration process could actually prove even more consequential.

"Regulatory agencies have to ensure a drug is being made the way it’s supposed to be made and made available to the patients in a safe and efficacious way," Felse said. "If regulatory science is not in place, you’re going to have drugs that are not safe."

The classic example of this is thalidomide, a German-developed drug in the 1950s that was used as a treatment for a host of ailments, including morning sickness in pregnant women. Researchers gave the drug to test animals and found no adverse effects, and soon after, it was determined the drug would be safe for humans.

By the middle of the decade, thalidomide was sold under dozens of different names in more than 45 countries. In Germany, it was available over the counter without a doctor's prescription.

At that time, there was no clear knowledge about how a drug taken by a pregnant woman would impact her fetus, nor was thalidomide ever tested on pregnant women. The results of this oversight were catastrophic: over the course of roughly five years, an estimated 10,000 babies were affected by the drug — approximately half died within months of being born. Those who survived faced a litany of physical obstacles, from facial disfigurement and damage to the brain to the shortening or complete absence of their arms and legs.

Thalidomide never made it to the United States because it was not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

But the US faced its own challenge around the same time with a polio epidemic.

In 1952, almost 60,000 children were infected with polio — 3,000 died and thousands more were paralyzed. A vaccine was developed in 1955 and quickly distributed across the country. Unfortunately, doses produced at Cutter Laboratories in Berkeley, Calif., actually contained the infectious virus instead of the vaccine. More than 200,000 children received the defective virus — tens of thousands became ill, 200 were paralyzed and 10 died.

These two incidents played a major role in shaping the regulatory science that exists today, Felse said. "Regulatory science has existed for years, but it's become a more defined discipline in the last 10 years," he said. "The field involves developing methods, tools and techniques to get healthcare products approved and available to patients in a safe and efficacious manner."

That process includes phased human trials and a registration period that falls between when a drug is approved and when it is made available to the public. During this period, regulatory agencies such as the FDA look to determine whether the drug company can make its drug safely and efficaciously. Do they have the facilities required to make such a large number of doses? If new facilities are required, who will build them and be on the production staff? How will they acquire the adequate number of syringes and other delivery to go along with the vaccine?

Countless other questions remain related to the development of a COVID-19 vaccine, including the prioritization during deployment. What countries will get the vaccine first? Within each country, what demographic populations will receive the initial doses? The biggest question, though, is the one Felse hears all the time: When will a vaccine be readily available for everyone?

His simple response is this: It takes time.

"A vaccine’s general timeline for development is three to five years, and we’re trying to get this vaccine done in less than a year," Felse said. "You can only shrink the timeline so much."

Now that the vaccine candidates are going through expedited approval in the US (Britain began offering its approved vaccine to individuals on December 8), the next big challenge will be mass production, distribution and supply chain logistics. Distribution logistics will vary significantly between countries depending on existing supply chain capacities. Until the population is sufficiently inoculated it is important to follow all pandemic safe practices such as wearing masks, social distancing and limiting travel.

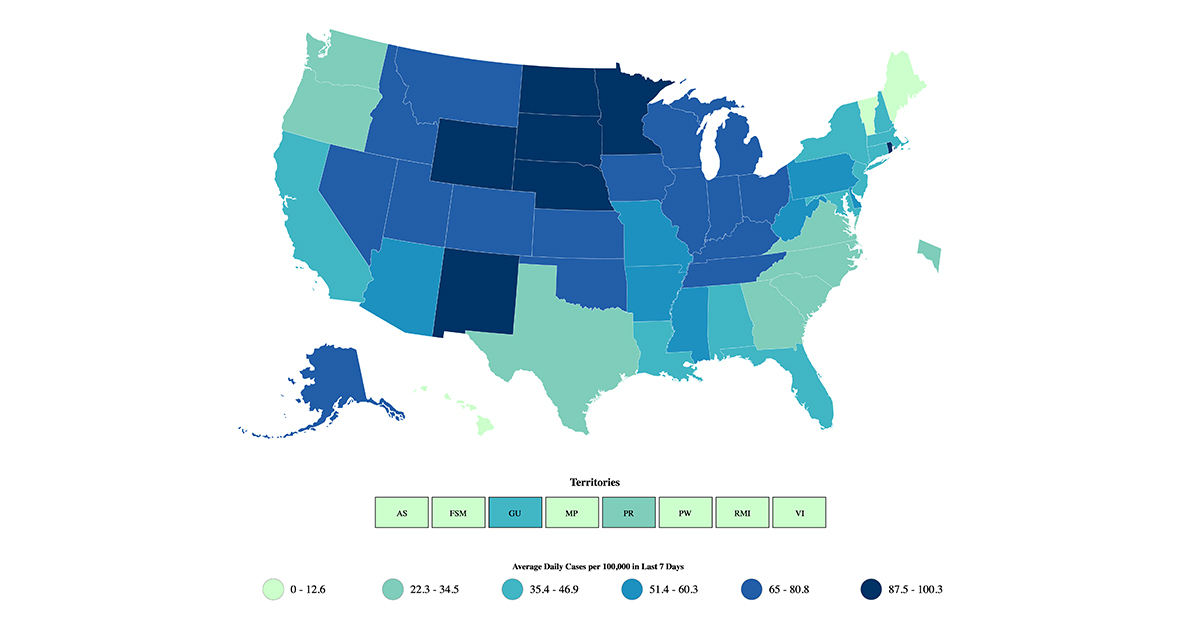

(Map downloaded from the CVC COVID Data Tracker)