Turning the Tide

Northwestern Engineering researchers develop technologies to protect, manage, and recover resources from our water supply.

Water—essential to life and fundamental to society—has become increasingly more threatening and under greater threat. People everywhere struggle to mitigate the effects of harmful pollutants that contaminate the water supply; droughts that endanger reserves for drinking, agriculture, and energy; and flooding and erosion that undermine infrastructure and the safety of communities.

Worldwide, nations and communities grapple with how to secure safe, reliable supplies of this most essential resource and how best to control and harness its full potential. Because of the complexity of these challenges, no single field of expertise has all the answers, and sometimes, just as water itself is known to do, research done in one discipline flows naturally into another.

Close to home

At Northwestern Engineering, research teams are detecting and removing contaminants from water supplies and studying how to put those contaminants to new and better uses. Some are discovering more efficient ways to use water for energy while their colleagues are devising methods for combatting water’s power for destruction.

Their collective work benefits from a natural laboratory just steps from campus—Lake Michigan, one of the world’s largest freshwater systems. “We have this incredible resource right in our backyard,” says Aaron Packman, professor of civil and environmental engineering. “It gives us both the opportunity and the responsibility to develop solutions that matter locally, nationally, and globally.”

Another factor nearby helps move University research into practical application: the City of Chicago’s ambition to become a hub for water innovation. Collaborations with local water management experts and access to local resources create channels for municipalities, companies, and community groups to adopt University-developed technologies and strategies.

“We are front and center not only with the greatest resource we have on the planet, but also in confronting the issues,” notes Julius Lucks, Margery Claire Carlson Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering.

A Low-Cost Test for Contaminants

Though proximity to Lake Michigan means Northwestern’s local community has plenty of fresh water to draw from, more than 2 billion people worldwide lack access to safely managed drinking water. Millions more live in places where water quality is uncertain or untested. These communities have an urgent need for a simple, affordable way to detect contaminants before they cause harm.

At Northwestern, Lucks has led the development of a portable, low-cost solution for detecting contaminants in water: ROSALIND. The platform uses synthetic biology to create “cell-free” reactions—biological components extracted from cells that can be freeze-dried onto paper or other materials. When these components are rehydrated with a water sample, they react to the presence of specific contaminants by producing a visual signal, often a simple color change.

ROSALIND can be programmed to detect a wide range of targets, from heavy metals, like lead, to bacterial pathogens. Because the reactions are cell-free, the system does not require live organisms, refrigeration, or complex lab equipment, which makes it well-suited for field use even in resource-limited settings. The Northwestern team also designed the system to be user friendly, with results that can be interpreted without specialized training.

“What ROSALIND allows you to do is take the power of biology and put it in anyone’s hands to understand their water,” Lucks says.

Soaking Up Pollutants

Detecting pollutants in drinking water is one obstacle. Clearing them out from both freshwater sources and oceans remains another challenge.

Heavy metals, microplastics, phosphates, and other contaminants not only make water unsafe for humans, they also disrupt ecosystems, harming aquatic life in lakes and oceans.

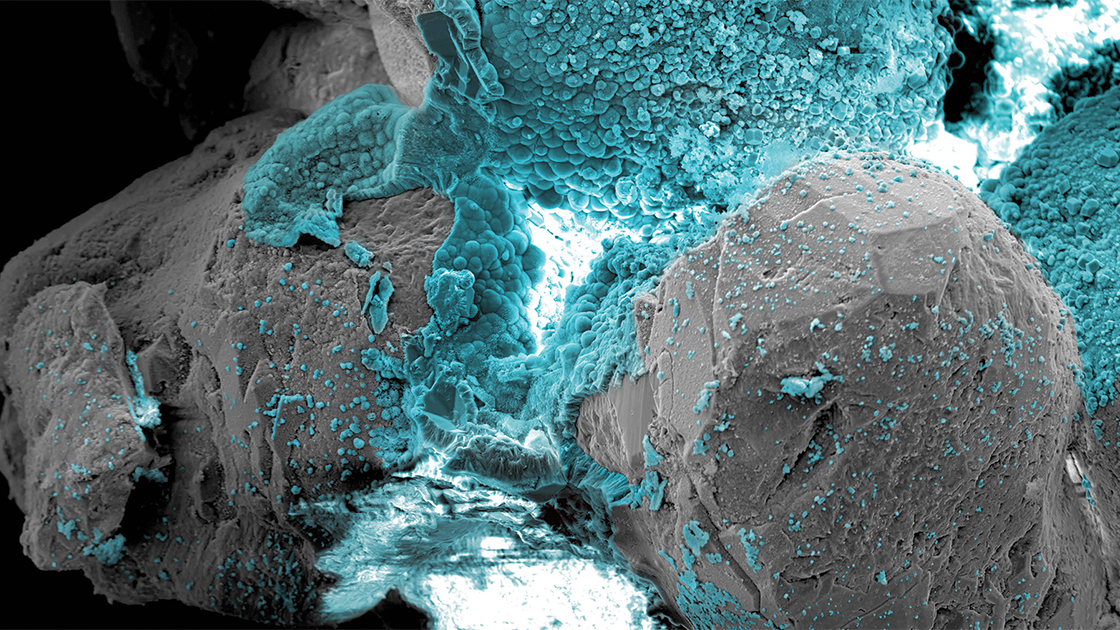

Professor Vinayak Dravid’s team has developed reusable, low-cost sponges that can improve water cleanup efforts. Coated with nanoparticles, the sponges have a high affinity for pollutants. Nanotechnology is key to their effectiveness: By reducing material size, the available surface area for capturing contaminants increases dramatically, enabling “Swiss-knife” solutions that can be tailored for a wide range of pollutants, including microplastics and oil.

“Nanotechnology allows us to impart specific affinity to capture pollutants that can be tailored to different pollutants,” says Dravid, Abraham Harris Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, who also cofounded Coral Innovations, a Northwestern startup commercializing the lab’s sponge-based reusable sorbents. “Our innovation anchors nanoparticles on pore surfaces of widely available sponges and foams for easily deployable technology at a large scale.”

Recovering Valuable Resources

Pollutants aren’t the only materials that can be extracted from water. Valuable minerals and chemicals like nitrogen can be collected and reused.

Jennifer Dunn, professor of chemical and biological engineering, analyzes existing methods to develop new, sustainable approaches for recovering and then reusing high-value minerals and elements in wastewater. One area of focus has been on recovery of copper, cobalt, nickel, and rare earths from mining wastewater. Her work not only mitigates some of the environmental impacts of mining operations, it also addresses the high demand for these minerals in sectors like communications and energy storage.

Another area of promise is producing animal feed from wastewater nutrients such as nitrogen and potassium. This could lessen demand for crops like corn and soy, freeing farmland for carbon-sequestering uses.

In her work, Dunn considers the life cycles and materials used in emerging water-sustainability technologies, evaluating their cost competitiveness and environmental impact. She sees synthetic biology as one promising tool for improving these processes.

For example, engineered enzymes or cell-free systems could be designed to selectively capture specific minerals, recover nutrients under gentler conditions, or ready these byproducts for new uses—transforming nitrogen waste into feed products, for example—in ways potentially more energy efficient and cost-effective than conventional methods.

“We consider cost competitiveness, environmental performance, and social aspects of different types of technologies that can solve linked challenges of water pollution and increased demand for valuable materials in wastewater like nitrogen and minerals,” Dunn says.

Creating Clean Fuels

Associate Professor Linsey Seitz is exploring ways to harvest yet another useful element from water: hydrogen, a clean fuel alternative.

When used as a fuel, the only byproducts of hydrogen are water vapor and heat. Hydrogen is also widely used as a commodity chemical, but scientists and engineers are still searching for better ways to produce it.

Water electrolysis—splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity—could offer a path forward, but current processes are energy intensive and expensive. Seitz is working to find better and cheaper catalysts for this reaction. Her research on iridium-based oxides, the most promising studied catalysts, enabled the design of a novel catalyst that maintains higher activity, longer stability, and more efficient iridium use, a finding that could make green hydrogen production feasible.

“Now that we finally know the nature of these active sites at the surfaces of the materials, we are designing future catalysts to achieve optimized performance and reduce or even completely eliminate the use of precious iridium,” says Seitz, associate professor of chemical and biological engineering.

Stopping Coastal Erosion

While some researchers study how to harness the energy from water, Alessandro Rotta Loria, Louis Berger Associate Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, is working to stop its destructive power for erosion.

He developed a method that uses a mild electric current to transform loose sand into a rock-like material, offering a sustainable alternative to conventional coastal protection. In lab tests, only a few volts were needed to cement marine sand.

Seawater’s natural supply of dissolved ions enables the process: When a small current passes between two electrodes, minerals such as calcium carbonate and magnesium hydroxide form around the cathode immediately. The process stops when the current is turned off and is even reversible, if necessary, by reversing the electrodes to redissolve the minerals.

“The aim of this work was to develop an alternative method capable of strengthening soils and porous materials more broadly—including rocks, ceramics, concrete, and even biological materials such as bone,” Rotta Loria says.

The method is also cost effective at about $6 per cubic meter, thanks to minimal current densities and low-cost electrodes.

Charting the Future of Water Research

Many McCormick School of Engineering teams are increasingly using AI and advanced sensing technologies to gather high-resolution data and forecast potential problems.

“Northwestern’s investments in AI will boost efforts to use sensing and data science to solve water challenges, opening doors that were previously locked because we lacked the insights these new data and algorithms will provide,” Dunn says.

Projects underway include developing real-time contaminant monitoring systems, creating predictive analytics for water utilities, and integrating circular water systems into industrial operations. These efforts often involve field trials where technology is tested in real-world conditions before being scaled up.

By combining AI, advanced sensing, and interdisciplinary expertise, these projects turn data-driven insights into practical solutions, ensuring that new technologies can be effectively tested, implemented, and scaled to meet complex water challenges.

“We’re facing problems that don’t have single-discipline answers,” Packman says. “The work we’re doing now—building connections, developing technology, and creating pathways for adoption—is about making sure we have the capacity to respond when those new challenges arise.”