From Atoms to Innovation

Northwestern engineers are leading the way in applying predictive, data-driven methods to reshape materials design and manufacturing.

For much of history, human beings have developed new materials through one process: trial and error. Those days have passed. Modern materials design has become both predictive and data driven.

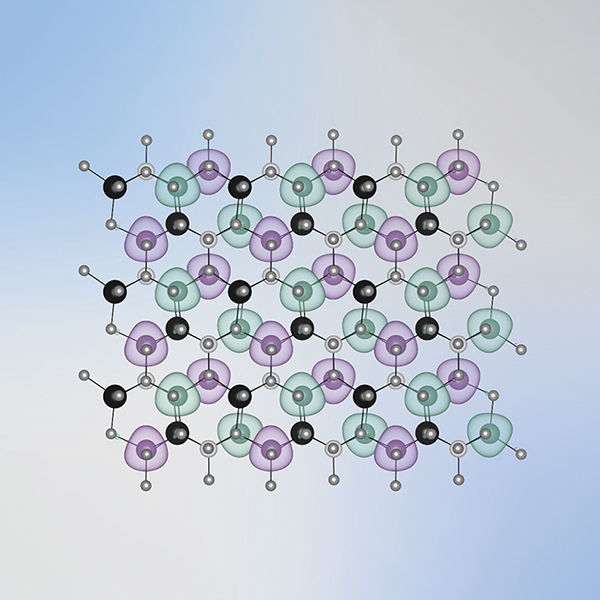

Today’s researchers start with a deep understanding of atomic and molecular structures, using quantum-mechanical models and AI to forecast how changes at the smallest scale will affect macroscopic performance. This approach reduces development time, minimizes costly failed experiments, and enables the creation of materials with properties that would have been difficult or impossible to achieve using conventional methods.

Northwestern Engineering scientists and engineers are at the forefront of this work, using insights from atomic-scale structures to guide the development of materials with improved performance and tailored properties. Their work moves fluidly among computer simulations, laboratory experiments, and factory-floor processes.

The result: new materials that make batteries longer lasting, computers more efficient, aerospace components lighter, and structures stronger and more sustainable.

From Simulation to Substance

Creating new materials begins by combining the power of computation with huge datasets. Chris Wolverton, Frank C. Engelhart Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, screens vast numbers of known and hypothetical compounds for properties like stability, performance, and sustainability. By simulating how these materials perform under real conditions, his team can focus on only the most promising candidates to synthesize and test.

Professor James Rondinelli takes a different approach: using quantum mechanical calculations and symmetry analysis to design materials with targeted electronic, optical, or magnetic properties.

These two researchers offer examples of an integrated model for materials design—one that starts in the digital space, narrows the possibilities with precision, and accelerates the path from discovery to manufacturing.

“If you can know ahead of time which materials are going to work and which aren’t, you can save an enormous amount of time, money, and resources,” Wolverton says.

That ability to pinpoint the right materials early is matched by the breadth of expertise across the University, spanning every stage of the design process.

“We have researchers across Northwestern who operate at all different length scales of materials design,” says Rondinelli, Walter Dill Scott Professor of Materials Science and Engineering. “Success in moving through the continuum from concept to commercialization really relies on having experts that can interact at every level.”

Designing for Strength

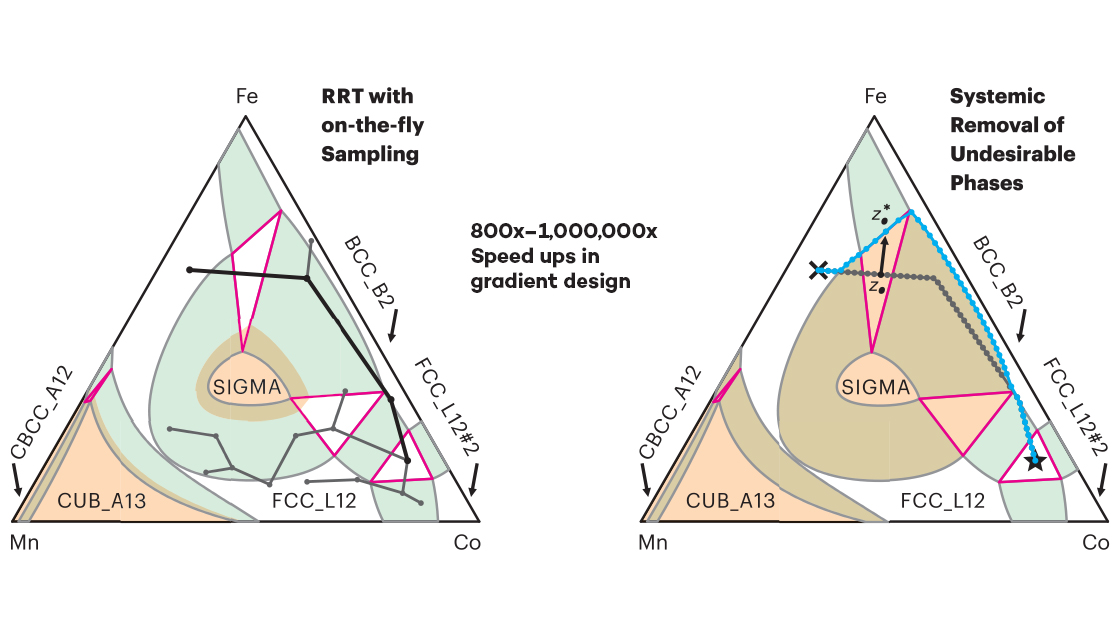

In many engineering fields such as aerospace, lightweight yet stronger materials can offer a significant advantage. With this in mind, the McCormick School of Engineering’s Ian McCue developed a computational framework to rapidly identify optimal composition gradients between dissimilar materials that avoid deleterious phases, enabling the creation of stronger, lighter multi-material systems.

“Optimal solutions to practical problems can be generated in a matter of hours rather than weeks or months,” says McCue, Morris E. Fine Junior Professor in Materials and Manufacturing.

While McCue’s work accelerates the design of stronger, lighter materials, understanding how those materials perform under real-world conditions is equally crucial. A group led by postdoctoral researcher Luciano Borasi in the lab of Dean Christopher Schuh developed a method to evaluate a material’s hardness across 11 orders of magnitude in strain rate. From slow deformation over minutes to impacts occurring in billionths of a second, the methodology unifies multiple experimental techniques within a single framework that applies consistent definitions.

This new approach could improve materials design and modeling to help ensure optimal materials are used for specific needs. “Now we can provide much more data and improve their accuracy,” Borasi says.

Designing for Sustainability

Materials design challenges us to think bigger picture about our work—to not, for example, only design the best battery, but also the most sustainable and recyclable one. Assistant Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering

As reliance on clean energy sources like wind and solar increases, so does the need for better batteries to store that energy. One way to design better batteries is to use different materials that can store more charge.

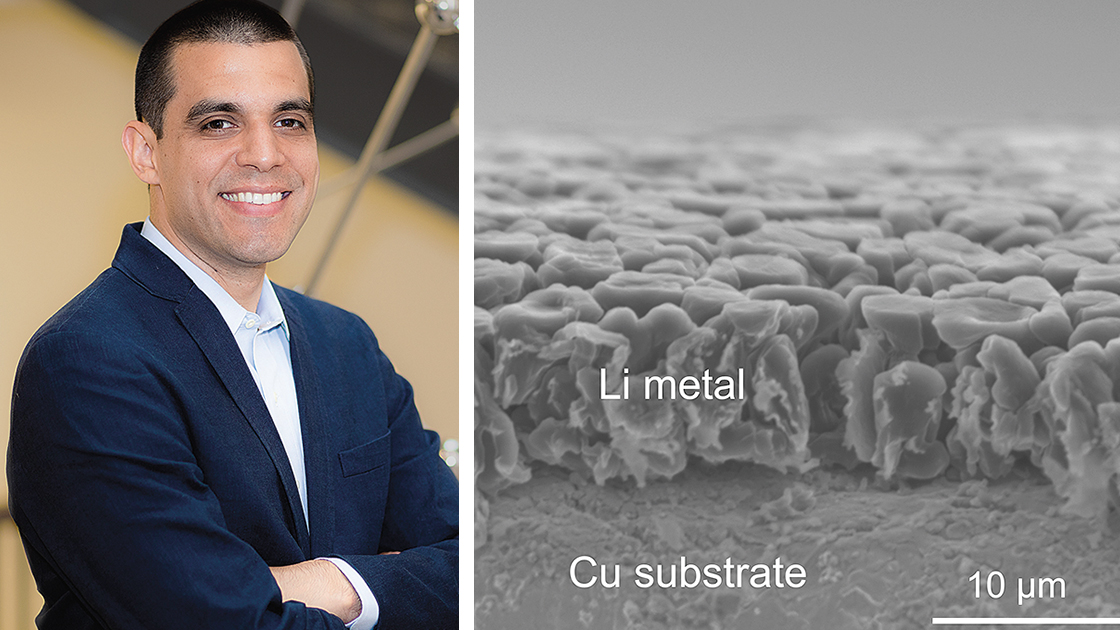

Lithium metal anodes are great for storing energy but react poorly with the electrolyte in batteries, causing instability. Many researchers have made progress solving this issue by adding stabilizing fluorine-based chemicals to the electrolyte, but these are “forever chemicals” or PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) that don’t break down in the environment.

To address this, Professor Jeffrey Lopez’s team is developing new electrolyte materials that work just as well—without relying on PFAS.

“Materials design challenges us to think bigger picture about our work—to not, for example, only design the best battery, but also the most sustainable and recyclable one,” says Lopez, assistant professor of chemical and biological engineering.

Designing for Performance

Building on efforts to make batteries more sustainable at the chemical level, researchers are also looking inside batteries to see how materials behave during manufacturing and use—with the goal of designing batteries that perform better and last longer.

As engineers, we’re looking to minimize the impact of our products and manufacturing processes on the environment.

Jeffrey RichardsAssociate Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering

Professor Jeffrey Richards currently leads a US Department of Energy-funded project that uses neutron scattering—a powerful technique that requires a nuclear reactor—to peer inside the electrodes of lithium-ion batteries at the nanoscale, observing physical and chemical changes during manufacturing and operation. The properties of neutrons allow them to pass through these materials without causing structural damage, ideal for revealing critical changes during battery operation. By better understanding how and why batteries fail, scientists will be able to develop a more accurate framework for designing battery materials with improved performance and lifespan.

“As engineers, we’re looking to minimize the impact of our products and manufacturing processes on the environment,” says Richards, associate professor of chemical and biological engineering.