A Precious Mission

Carolyn Duran ensure that the metals in Intel's microprocessors do not come from mines run by warlords.

If you could nominate women to be real-life superheroes, Carolyn Duran would certainly make the cut.

Not many people, after all, can take personal credit for the plummeting profits of warlords in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a country devastated by years of bloody conflict and human rights atrocities.

Duran’s mouthful of a title at Intel Corp. — director of global supply management, supply chain corporate social responsibility and lithography commodity management — hardly hints at the global impact of her work since she earned her doctorate in materials science and engineering from the McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science in 1998.

Duran’s mouthful of a title at Intel Corp. — director of global supply management, supply chain corporate social responsibility and lithography commodity management — hardly hints at the global impact of her work since she earned her doctorate in materials science and engineering from the McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science in 1998.

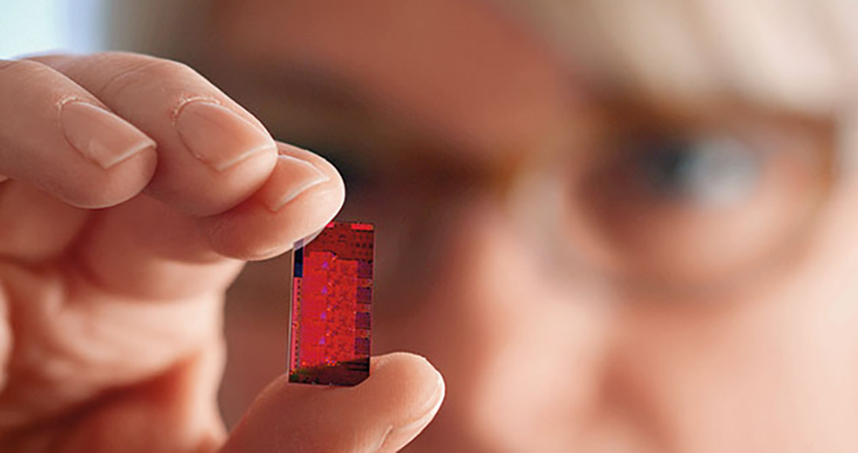

As head of the conflict minerals program at Intel, she and her team have meticulously traced the source of metals used to make Intel microprocessors. And they helped create an industrywide program to ensure that none come from mines controlled by armed groups that have been killing, raping and displacing millions, often using child soldiers to do their dirty work.

After years of Duran’s hearing people tell her it could not be done, Intel declared its microprocessors conflict free in 2014 and that it will make all company products conflict free by 2016.

That means that when you buy mobile phones, tablets or computers that use Intel chips, you won’t inadvertently be funding a civil war that is “one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises over the last 20 years,” according to Sasha Lezhnev, associate director of policy at the Enough Project, a Washington, D.C.–based nonprofit battling genocide and crimes against humanity in Africa. (See Duran and Lezhnev discuss the situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo.)

“It’s humbling,” Duran says. “When we started the conflict minerals program I never would’ve thought that I’d have an opportunity to participate in something like this or be capable of it. It’s really amazing. I stumbled into this and I am so grateful that I did.”

Duran is accomplishing this feat, by the way, while raising three young sons and, recently, battling breast cancer.

“She’s dauntless,” says her boss Jackie Sturm, vice president of technology and manufacturing and general manager of global supply management at Intel. “She brings a level of positivity even to problems we have no idea how to solve. … She just makes stuff happen.”

Duran never set out to change the world — at least not in terms of geopolitics or human rights. Born in Chicago and raised in a small coal-mining town in rural Pennsylvania, she is the daughter of a welding supplies salesman and a mom who worked various retail jobs.

Few people in her high school even went to college, and while she showed an early aptitude for math, her guidance counselor suggested she become a nurse.

“Not even a doctor,” she says. “That didn’t sit well with me. I faint at the sight of blood, and my only B in high school was in biology. Why on earth would she say that to me?”

Describing herself as “stubborn,” Duran did not let bad advice get in her way. She decided to study materials science and engineering at Carnegie Mellon, and, with thoughts of becoming a professor, she went on to get her doctorate at Northwestern.

Under the tutelage of adviser Bruce Wessels, Walter P. Murphy Professor of Materials Science and Engineering and Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Duran worked on superconducting thin films. She describes Wessels as “a tough guy” who prepared her well for her future career.

“I really appreciate the education he gave us, and not just the science. He came from industry, so he ran his group with some expectations that were a little more industry oriented,” Duran says. “He made it really easy to come to Intel, which is also a tough work environment. He really made you stand up for yourself and fight for your thesis.”

Wessels never let students drift through the lab, Duran says, but instead required weekly reports on their progress, with expectations of practical results. She wound up finishing her doctorate in 4.5 years and was immediately recruited by Intel.

Wessels remembers Duran for her determination in the lab. “She was working on a difficult problem of a multicomponent superconductor, which means it had many chemicals in it. I remember how tenacious she was about getting the compositions right and understanding how to do it.”

While she was a “talented student,” she “had quite a personality outside the laboratory too,” he adds. “She was outgoing and made friends easily. She was sort of a leader in the group, and she also made an effort to do more than just the science.”

After joining Intel in 1998, Duran spent nine years working in the research and development lab, earning five patents for developing new technology. But her desire to work with people outside the lab and take on a broader challenge led her to move to the supply chain side.

“That will always be me,” Duran says. “I want to learn deeper and wider, deeper and wider.”

What she soon learned about Intel’s supply chain was unsettling. Four metals used in Intel chips — tin, tungsten, tantalum and gold — could be mined in the DRC, and armed groups controlled most of the mines and wreaked havoc on the country.

“Somewhere in the neighborhood of 6 million people have died as a result of the war,” Enough Project’s Lezhnev says. “Some of the worst atrocities that you can imagine have been perpetrated on the DRC. There are tens of thousands of child soldiers, and hundreds of thousands of women have been sexually abused, including children. And minerals have really been one of the main drivers of this conflict.”

After the Enough Project brought the issue to the attention of the company’s then–chief operating officer and now-CEO Brian Krzanich, Intel created a team in 2009 to work on the problem.

According to company lore, when Krzanich first heard of the potential for metals used in Intel’s chips to be funding atrocities in the DRC, he had a very emotional, personal reaction — and proclaimed that Intel had to do something.

Duran took over the team in charge of the project a year after it was formed, set some concrete goals and then had to find a way to turn them into a reality, which was easier said than done. Intel products are made from metals sourced from thousands of mines scattered across the globe, and tracing every one would require a level of detective work worthy of Sherlock Holmes.

But Duran believes she and her team got “lucky.” They quickly determined there is a pinch point in the process. Every metal mined has to go through a smelter to melt it down and turn it into a product pure enough to be used for industry. And while there are thousands of mines around the world, there are only several hundred smelters processing metals for Intel chips, a much more manageable number — and a part of the process that simply could not be skipped.

The Intel team helped create a third-party auditing system, the Conflict-Free Smelter Program, which requires smelters to document where they received their metals from and prove that none came from conflicted mines.

Duran and her team spent the next few years meeting with nearly 100 smelters in 21 countries, educating them about the problem and twisting their arms to join the program if they wanted to continue selling to the company. Duran and her team are part of a broader coalition of technology companies, such as Motorola and Apple, that joined with Intel to increase their collective leverage.

When Intel announced in 2014 that the entire company would go conflict free, Enough Project “got calls from many, many companies saying, ‘We want to work with you to make sure our products are conflict free too,’ ” Lezhnev says. “All of a sudden, it set off a business competition — which is healthy, I think — to achieve the goal of making the whole industry conflict free.”

Soon the Conflict-Free Sourcing Initiative, a resource created in 2008 by members of the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition and the Global e-Sustainability Initiative, began attracting other industries, such as aircraft manufacturers. That process was helped by the passage of the Dodd-Frank financial reform law in 2010, which requires public companies to disclose whether they are using conflict minerals.

“There’s been a lot of progress,” says Duran, who chairs the CFSI steering committee. “Some of that was driven by the legislation, so the Boeings of the world are now subject to this. If they weren’t interested before, they’d have to be interested now. The Conflict-Free Smelter Program, which was started in the electronics industry, now has seven or eight different industries represented and more than 200 different members.”

The biggest factor in getting other industries on board, though, was demonstrating that going conflict free was possible, Duran says.

“Somebody’s actually got to put their neck out there and say, ‘I’m going to do it’ and show people it can be done, because a lot of folks were saying, ‘This can’t be done. You can’t have your supply chain to this level,’ or ‘You’ll never get to where you need to go.’ ” (Get a look inside Duran's work at Intel.)

Intel did most of that hard work of convincing smelters in places such as China and Indonesia to get with the program — a process rife with language and cultural barriers in countries that didn’t always have the same respect for human rights.

The worlds of high-tech manufacturing at Intel and that of the smelters could not be more different, Duran says.

“I was at a smelter in Indonesia, and literally there are no sides to the walls,” Duran says. “There’s a roof, there’s a big furnace that’s the size of maybe three cars. And they’re dumping in this crushed rock, which has some high percentage of tin in it, melting it, and out the other end of this long machine, you’d get this molten metal pouring out. And there are these guys standing in this immense heat in these dirty dungarees because they’re dealing with hot molten metal. I mean, it’s just dirty work.”

At Intel, on the other hand, chips are made in class 10 clean rooms, “which means there’s 10 particles of dirt in a square foot, period,” Duran says. That’s 1,000 times cleaner than the air in a hospital operating room. “You have to wear what they call ‘bunny suits’ because we are dirty, and one little speck of anything will kill the chip. It’s fully automated, and you can’t touch anything. Everything’s isolated because it’s so clean.”

For smelters that processed minerals from mines thousands of miles from the DRC, there was often confusion over why Intel was talking to them about militias in Africa.

“Let’s just say it’s a recycling tin refiner in Belgium,” Duran says. “They’re like, ‘Why are you contacting me? I don’t take anything from the Congo.’ But we had to have every smelter stand up and show where their stuff came from to weed out the places who weren’t sharing [the information]. You had to flush ’em out, basically.”

Despite difficulties, Duran was persistent. The first smelter was audited in 2010, and today more than 60 percent of the world’s smelters for gold, tin, tungsten and tantalum have been declared conflict free. Another 10 percent are in the process of being audited.

“Intel’s work has made a major impact on reducing the trade in conflict minerals,” Lezhnev says. “They have really started a revolution in corporate supply chain, in terms of garnering more transparency not just in their supply chain but really moving the industry on this issue.”

As a result, “change is starting to happen,” he adds. “Armed groups are making less. Over 70 percent of the tin, tantalum and tungsten mines in the Congo are now conflict free, as opposed to five years ago, when nearly every mine was controlled by an armed group or the Congolese Army. That is a pretty major change that has happened on the ground.”

Moreover, Intel went conflict free without entirely pulling out of the DRC, which would have hurt the small artisanal miners attempting to make an honest living.

“That’s one of the only means of survival they have in the region,” Duran says. “We didn’t want to hurt people who had been through so much — decades-long human-rights atrocities — and then just kick them again. For us it was more important to try to have a system in place so we could buy from conflict regions but [ensure that it was] conflict-free material. It was a conscious decision to do that.”

There is still work to be done. While the electronics industry is the primary user of tantalum, gold has proven to be a tougher problem because jewelry and investment banking are much larger users. With widespread government corruption in the DRC, there is still some metal smuggling and stealing of tags that label the metals conflict free.

“No one can ever say with 100 percent certainty that at every point in time, every single chip we make is not somewhere from conflict,” Duran says. “But if you keep waiting for that perfection, then you never would start. You’d never have anything.”

Given her success on conflict minerals, Duran was promoted in January, taking on a broader sustainability and corporate social responsibility role at Intel, as well as other duties.

“There’s a lot of stuff in the papers today about forced and bonded labor, modern-day slavery,” Duran says. “Who is actually making your clothes or your coffee or electronics? That transparency is a new expectation, but I think it’s an expectation that we as a society need to have.”

Duran likens it to the farm-to-fork food movement and believes it is a necessary reaction to globalization.

“A hundred years ago everything was made right in our own countries, and then we swung to this huge global economy where everything was made somewhere else,” she says. “And we turned a blind eye to how those things were being made somewhere else. And now the pendulum is swinging hopefully toward a nice middle state where we see this balance. That’s just really thinking about the total cost of ownership, and it doesn’t just mean the price you pay, right? It means the whole thing and how it got there.”

Three months after taking on this broader role, doubling her responsibilities and the number of employees on her team, Duran learned she had breast cancer. Despite dealing with hair loss, watery eyes and brain fog, though, she took just a few days off after each chemotherapy treatment and chose to continue working full time, at a scaled-back schedule of about 45 hours per week.

“It’s pretty phenomenal to see her dedication, despite her major health challenges, to actually continue working on this,” Lezhnev says. “I don’t know if I would be able to do the same thing if I were in the same situation.”

Duran says her prognosis is excellent and working actually helps. “My mind moves all the time, and it needs to have a good positive place to move. Focusing on cancer is not a positive place to move, except to get through it.”

It helps that her husband, Terry Franks, an architect who works part time from home, is the primary caretaker of their 8-year-old and twin 5-year-old sons. “He’s definitely been awesome through all of this,” she says. “He’s a keeper.”

The knowledge that she is making a difference also fuels her. “I love what I do, and that helps a lot,” she says. “It’s really rewarding, the fact that we could do this and demonstrate that it could be done. … I’m not going to sit still.”