Northwestern Scientists Publish Guiding Principles for COVID-19 Vaccine Development

Four takeaways from research could help scientists working to develop safe and effective vaccine

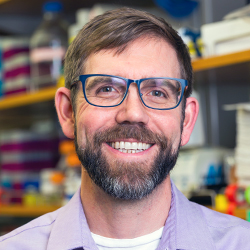

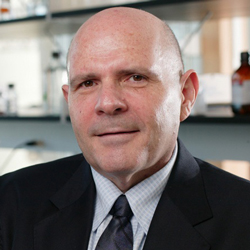

A team from Northwestern including Northwestern Engineering’s Michael Jewett and Samuel Stupp has created guidelines to assist in developing a safe and effective vaccine for COVID-19.

Published July 21 in ACS Central Science, the principles were gleaned from early research on COVID-19 and data from the 2003 SARS outbreak, caused by SARS-CoV, a very similar virus to SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19.

There are four important takeaways from the research:

1. A COVID-19 vaccine must strike a delicate balance.

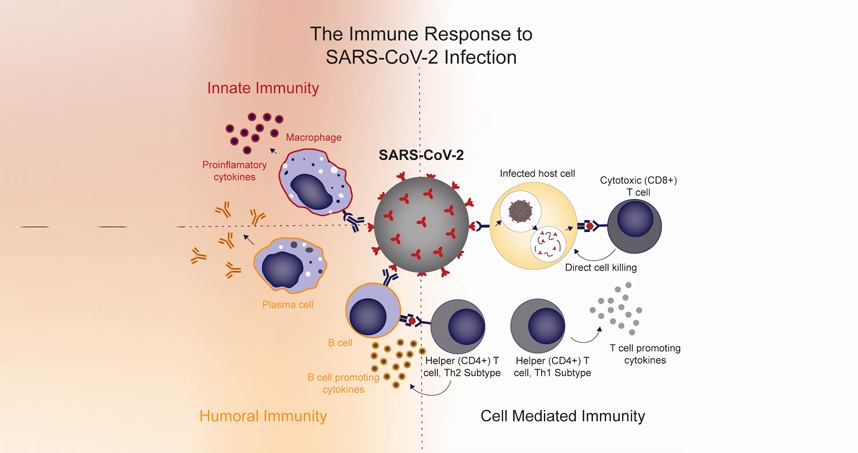

In the case of COVID-19, studies have shown that a broad immune response may trigger inflammatory processes that damage the lungs, leading to acute lung injury. A successful vaccine will likely require eliciting specific antibodies — proteins that respond to and neutralize pathogens — and T cells without invoking a large-scale inflammatory response.

A strong T cell response has been associated with both clearing the virus and guarding against lung injury. T cells may also help the immune system “remember” the virus for longer periods of time than antibodies alone, so a vaccine’s ability to activate this response could be a key factor in long-term protection, the authors determined. Monitoring for a T cell response to a vaccine is much more challenging than monitoring for an antibody response, but it may be critical in measuring true COVID-19 protection.

A strong T cell response has been associated with both clearing the virus and guarding against lung injury. T cells may also help the immune system “remember” the virus for longer periods of time than antibodies alone, so a vaccine’s ability to activate this response could be a key factor in long-term protection, the authors determined. Monitoring for a T cell response to a vaccine is much more challenging than monitoring for an antibody response, but it may be critical in measuring true COVID-19 protection.

“To prevent lung injury, you want to elicit an effective immune response but nothing extra, so that you’re not activating a big cascade of immune processes that aren’t as helpful,” said Ariel Thames, an MD-PhD candidate in Jewett’s lab and first author of the paper. “By primarily eliciting a T cell response and getting that antibody specificity correct, you should be able to effectively clear the virus and circumvent any of these harmful effects.”

That’s not to say the process is easy. Even with the playbook offered by the Northwestern scientists, a successful vaccine will have to hit the correct parts of the immune system at just the right strengths.

“It’s finding a needle in a haystack, and it’s doing that under immense time pressures that frankly have not been seen in our lifetimes,” said Jewett, Walter P. Murphy Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering in the McCormick School of Engineering and director of the Center for Synthetic Biology at Northwestern. “Getting all of those bits right is what hopefully the framework of this article will provide, enabling scientists and perhaps even the non-expert to begin to understand how hard of a problem this is.”

2. Antigens and vaccine platforms provide opportunities to “tune” immune responses.

Strategically varying these two factors offers scientists the best chance to find the right combination for a safe and effective vaccine, said Jewett, corresponding author. Antigens are the molecules — often proteins — that are detected as a foreign substance in the body and can trigger an immune response. Vaccine platforms can take many forms, each of which causes the body to react differently.

Strategically varying these two factors offers scientists the best chance to find the right combination for a safe and effective vaccine, said Jewett, corresponding author. Antigens are the molecules — often proteins — that are detected as a foreign substance in the body and can trigger an immune response. Vaccine platforms can take many forms, each of which causes the body to react differently.

“You can have a viral vector vaccine, a nucleic acid vaccine, or protein-based vaccines, and all of those will activate slightly different parts of the immune system,” Thames said. “They all overlap in some ways, but some platforms will activate one branch of the immune system more strongly than the other.”

3. Clinical trialists should monitor for lung injury after vaccination.

Given the observation of immune-mediated lung injuries in patients and animal models with SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, the authors believe these conditions must remain top of mind for clinical trialists and medical professionals.

“We hope this article can positively influence medical practice,” Jewett said. “It can inform the evaluation of current vaccine candidates and clinical trial development, not just for COVID-19 but for other vaccines.”

4. COVID-19 data are ever-evolving — and so are researchers’ efforts to fight it.

Jewett said the manuscript took a few months to prepare and required weekly updating due to the endless deluge of new data. The authors aren’t claiming to know how to elicit the optimal immune response in a COVID-19 vaccine, but they believe the basic principles they’ve identified — based on the best available information to date — can help the scientific community eventually reach that point.

Jewett said the manuscript took a few months to prepare and required weekly updating due to the endless deluge of new data. The authors aren’t claiming to know how to elicit the optimal immune response in a COVID-19 vaccine, but they believe the basic principles they’ve identified — based on the best available information to date — can help the scientific community eventually reach that point.

“Having tens of vaccine candidates already in human clinical trials, and many in the pipeline, in just months — it’s really been remarkable,” Jewett said. “As scientists, this is one of our chances to try to transform the way we exist on the planet in the wake of a pandemic.”

Co-authors include Stupp, Board of Trustees Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, Chemistry, Medicine, and Biomedical Engineering and director of the Simpson Querrey Institute (SQI), and Kristy Wolniak, assistant professor of pathology at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. Both Jewett and Stupp are members of SQI.