The Problem

Current cell therapies like CAR-T cells lack the precision to distinguish between healthy and diseased tissue, leading to limited effectiveness and potential side effects.

Current cell therapies like CAR-T cells lack the precision to distinguish between healthy and diseased tissue, leading to limited effectiveness and potential side effects.

Researchers engineered a new class of synthetic receptors that allow therapeutic cells to detect specific biochemical signals in their environment and activate only in response to disease-related cues.

This could lead to safer, more targeted treatments for cancer and chronic diseases by ensuring that therapies are activated only when they are needed and precisely at sites of disease.

Professor Josh Leonard, doctoral student Amparo Cosio, former doctoral student Hailey Edelstein (PhD ’23)

One of the most significant breakthroughs in cancer treatment in the past decade has been the rise of CAR T-cell therapy: a form of personalized medicine where a patient’s immune cells are engineered to find and destroy cancer.

While this technology has shown remarkable success in some cancers, its reach remains limited. A key challenge is controlling when and where these powerful therapies activate, and a new study from Northwestern Engineering researchers could help change that.

A team led by Professor Joshua Leonard has developed a new class of synthetic receptors that can help cell therapies sense their surroundings more precisely. These smart sensors can detect biochemical cues that are often elevated in cancerous or diseased tissue, such as interleukin-10, a signaling molecule that regulates the immune response, and activate therapeutic functions only in those environments.

“Figuring out how to ‘teach’ cells to recognize specific molecular fingerprints that identify a site of disease is key to realizing the full potential of cell-based therapies,” Leonard said. “This study could ultimately enable the development of safer and more effective treatments for cancer and chronic disease using ‘smart’ cell therapies.”

A founding member of Northwestern’s Center for Synthetic Biology, Leonard is a professor of chemical and biological engineering at the McCormick School of Engineering and a member of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University. Leonard and his team detailed their work in the paper “Conversion of Natural Cytokine Receptors Into Orthogonal Synthetic Biosensors,” published Aug. 22 in the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

Joshua LeonardProfessor of Chemical and Biological Engineering

A decade ago, Leonard’s lab created a class of synthetic receptors called Modular Extracellular Sensor Architecture (MESA) receptors. Over time, the team has refined the platform to address new needs, improve performance, and generate new methods and insights into synthetic receptor engineering. This study leverages insights and technologies built through those efforts to create engineered cell prototypes that combine synthetic receptors with genetic circuits to build cells that perform useful and entirely novel functions.

The advance opens the door to more refined cell-based treatments, ones that don’t rely on brute force but instead act with precision. By engineering receptors that turn on only in the presence of disease-specific signals, the risk of harming healthy tissue can be reduced.

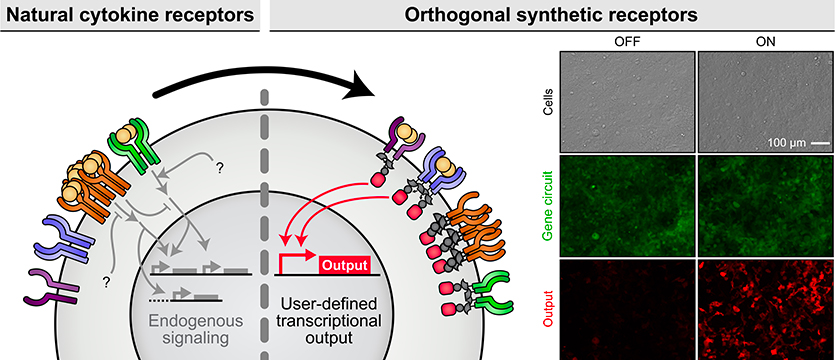

These new synthetic receptors, called Natural Ectodomain (NatE) MESA, are designed using components from natural human proteins called cytokine receptors. “Ectodomains are the parts of receptors that first come into contact with signals outside of the cell, in the body,” said Hailey Edelstein, who co-led the study with Amparo Cosio as doctoral students in Leonard’s lab. “We hypothesized that by incorporating natural ectodomains into MESA receptor technology, we could harness their inherent ability to detect specific signals and rewire them to build new functions.”

By converting natural cytokine receptors into modular, orthogonal sensors that operate independently from the body’s native pathways, researchers can program cells to perform specific actions, like releasing a cancer-fighting molecule or boosting immune function, but only when the right signal is present.

This logic-based approach mirrors how computers make decisions. In the study, Leonard’s team engineered cells that activate only when two separate disease cues were detected. These kinds of layered decisions are important for distinguishing complex disease environments like tumors from healthy tissues, and enabling cell therapies to make those decisions makes them safer.

The technology is also designed to be flexible.

“Given their modular, self-contained nature, these synthetic receptors can be employed for engineering a wide variety of cell types for diverse applications,” Leonard said.

This means the possibility of more effective cancer treatments that come with fewer side effects. It also opens opportunities for new therapies addressing chronic diseases or immune dysfunction, where treatments could be tuned to the unique signals present in diseased tissue without disrupting healthy cells.

“Intensive work is ongoing in our lab and in the field to make effective cell-based therapies accessible to more patients, and improved synthetic biosensors can help to realize these goals,” Leonard said.