Events

EventsThe Art in Bringing Humanity to Science

Artist Dario Robleto urges us to remember the humans hidden within scientific discovery

There is an unnerving sound embedded into two of Dario Robleto’s latest artworks. It’s a bleak drone that lives in a melancholy space between a hum and a whir, conjuring mental images of endless, barren skies and vast, abandoned landscapes.

It is the sound of the world’s first beatless artificial heart, quietly echoing from inside of a living human. Powered by whirling motors, the device spins, rather than pumps, blood through the body.

In 2011, Houston surgeons implanted the heart into Craig Lewis, a 55-year-old man dying of amyloidosis. Soon after, Robleto documented its unprecedented sound from inside another patient testing the device. Now, Robleto has unveiled the haunting reverberation as part of “The Heart’s Knowledge,” a new exhibition at The Block Museum of Art.

“It is the most complicated sound I have ever heard in my life,” Robleto said. “One of the doctors who developed it said it sounds like ‘an empty, windswept landscape.’ It’s very difficult to describe. You just have to hear it.”

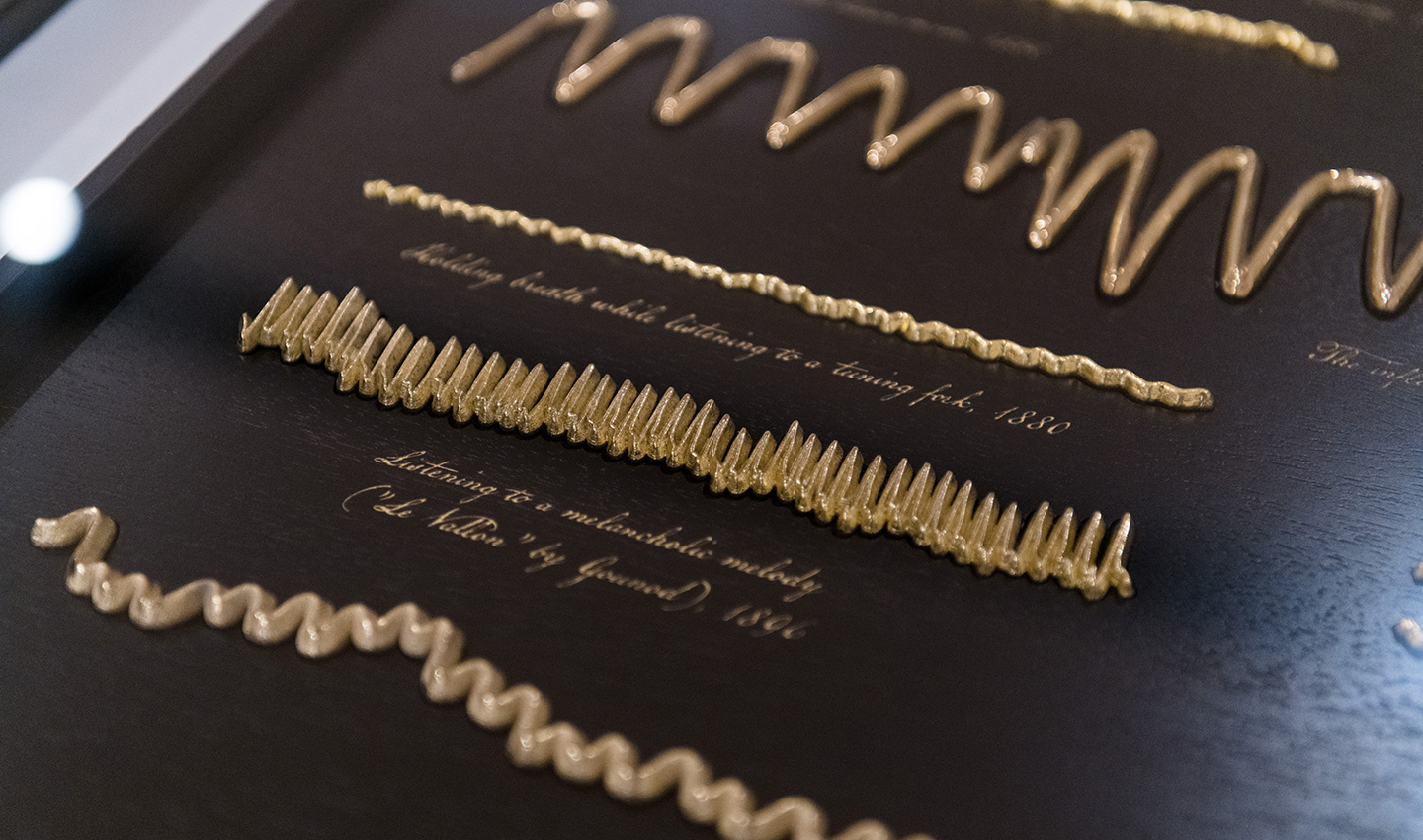

The story of the first beatless heart is just one of the deeply human — yet scientific — narratives in Robleto’s new exhibition. The multimedia feat also includes familiar thumps from the first-ever recorded heartbeat in 1854, the crackling brainwaves of a woman in love and a heartbreaking tale of a 19th-century physiologist who recorded brainwaves from a dreaming, dying child.

Weaving together these seemingly disparate stories, Robleto arrives at a rarely explored intersection, delicately hovering between science and art. Robleto uses film, sound installations, sculpture and prints to give viewers a multisensory experience that draws them closer to the faint traces of life buried inside the scientific record.

“These waves are not just medical data anymore,” Robleto said. “They are somebody’s lived experience. I want to merge those sensibilities together.”

The exhibition marks the culmination of Robleto’s five-year engagement as artist-at-large at Northwestern Engineering, where he regularly engaged with faculty members to expand conversations around ethics, empathy, curiosity and compassion. A self-described “citizen scientist,” Robleto contends that scientists and artists are driven by the same thing: To increase the sensitivity of their observations.

“One of the goals of science, as of art, is to peer into the unknown,” said synthetic biologist Julius B. Lucks, who worked with Robleto throughout his time with McCormick. “To understand the unknown, scientists must first use creativity to imagine new ways of how such pieces fit together and then use tools of the scientific method to prove or disprove their models of how the world works. Without creativity and imagination, there is no new science. Robleto has enabled us to journey outside our research expertise to imagine how our technologies may interface with and impact society.”

“The Heart’s Knowledge: Science and Empathy in the Art of Dario Robleto” is currently on display through July 9.

Robleto joined us to discuss his new exhibition, the inspiration behind it, and how hospice workers shaped his life from a young age.

One theme that runs through your work is the message to remember others. Why do we have that responsibility?

That’s the biggest, most important question to me. Humans are a unique species that have long-term memory that affects the way we choose to live our lives. What’s different about the human mind is that we’re aware of our own mortality. We have the power to remember — both in a sense of memorial and as a form of action because it inspires behavior. We can change our behavior because we care about our responsibility to those who have come before us. We hope the future will care about us in the same way. The succinct way I say it is: ‘If you remember, I will remember.’ It’s part of my philosophy in art making. Memory is the thread that connects us, and that connection matters. We owe it to each other to remember.

How do you illustrate this philosophy in your exhibition?

The particular narrative of the history of the heart illustrates this philosophy in a very direct way. We are responsible for each other’s hearts — both in a deeply poetic sense as well as a technological sense. The pulse wave interests me as an unexplored way that information is passed down. Thinking about Ann Druyan, who recorded her brainwaves for Voyager’s Golden Record. She had just fallen in love with her future husband Carl Sagan and was secretly thinking about her love for him while recording her brainwaves. She sneaked love on board of a spacecraft. In that moment, she was thinking about billion-year timelines as far as the obligation of memory to extend forward in time.

You dedicated ‘The Heart’s Knowledge’ to Ann, the creative director of NASA’s Voyager Interstellar Message Project. Can you tell us about your relationship with her?

I heard the Golden Record for the first time when I was seven. I was home sick from school, and Voyager was just marking five years of flight. It was approaching Saturn. By coincidence, I caught a program on TV, saying that NASA had released a 1-800 number to the public, where you could call in to hear sounds of space. In my little boy brain, sick with a terrible cold, I completely misunderstood this announcement as meaning that we made contact with aliens. In my enthusiasm, I wanted to call that number. When I did, I heard static. This confused me because I didn’t understand why aliens would send static. This deeply affected me for most of my life. I harbored curiosity about the mystery of this recording for years.

Everything on the Golden Record is an attempt to be clear — to clearly communicate the experience of life on Earth to future extraterrestrials who might find it one day. The static was an anomaly compared to the rest of the record. Why in the world was their static on board?

Fast forward to 30 years later, I appeared on the same episode as Ann on “Radiolab.” I was on a different segment, so I didn’t realize she was on the show until I listened to the episode. During the interview, she publicly revealed the story behind the static. She recorded her brainwaves while thinking about her love for Carl, wondering if aliens might one day be able to interpret her brainwaves to read her mind. Hearing this was one of the most profound moments in my life. I wanted to know more, and it led to this whole project. One question it inspired me to ask was: ‘What does one gift to the only woman whose heart has left the solar system?’ I worked for 10 years on this question, and this show is the answer.

While examining the history of the heart, you also looked forward to the future of the heart, debuting sounds from the first beatless artificial heart. What struck you about this invention?

Dr. Bud Frazier is a cutting-edge researcher, who I’ve worked with in Houston. He wants to cure the ramifications of heart disease and argues that we can’t overcome the challenge of designing a working artificial heart. People have tried to develop a total artificial heart for 60 years — one that can last a lifetime, if needed — and we still haven’t done it. He suggests that maybe we have failed because we are trying too hard to mimic the human heart, so he decided to start over engineering-wise and rethink this. Building off other innovations in his field, he came up with a continuous flow technology. It contains little rotor blades, spinning thousands of times per minute, held in space by powerful magnets.

I’m fascinated by this because it raises new ethical questions that nobody considered before. One of the foundational features of our humanity is that we have beating hearts. Are we OK with a future of beatless human hearts? I don’t know, but we should ask. Nobody’s ever fallen in love with a beatless heart. No artist has made art with a beatless heart. Nobody has worshipped their god with a beatless heart. It’s not a trivial thing that Dr. Frazier is tinkering with.

Mr. Craig Lewis volunteered to test this experimental technology in 2011. He is the first person in human history who was a flatline on every monitor in the room. He had no heartbeat, pulse or EKG. Yet he lived for five weeks. After surgery, his wife could not help but to wonder: ‘Do you still love me?’

Some of the stories that you tell in your exhibition are so heartbreaking. How do you deal with immersing yourself into these painful topics?

It’s hard. But I tend to be drawn to those stories. I don’t set out to tell tragic stories, but the questions I ask tend to lead me down that road. I have a motto I like to recite: Forgetting is a luxury that artists don’t get to have. I’m not arguing that everyone has to remember everything. But someone has to look at difficult things — to bear witness — and not blink. I take that seriously because it’s what the work asks of me.

My mother worked for a hospice facility for nearly 20 years, so I grew up around hospice nurses. As a little boy, I would sense what she went through every day, even if she didn’t voice it. I eventually worked for the hospice, too, and quickly understood all she had kept to herself. Any time we took on a new patient, my job was to coordinate getting equipment into the into the patient’s home. So, I was always on the phone with nurses, coordinating these things. Whenever a child entered hospice, everybody knew. One of my favorite nurses was with one child and didn’t leave his bedside until he passed away. The morning after he passed away, I knew this nurse was coming into the office. I was gripped with anxiety because I didn’t know what to say to her. But she beat me to it. She came into the office and came right up to my desk. With complete sincerity, she asked me, ‘Dario, how is your day going?’ She knew I was worried, and, somehow, even with the weight she was carrying, she still took the time to ask about my well-being. It seems so small, but I never forgot that exchange.

My model of being an artist formed right there. We have an endless capacity to care and empathize. So much of my current show is about pushing the boundaries of our empathy further than we thought possible.

How has this philosophy informed your conversations with McCormick faculty?

Ethical discussions are a wonderful way for humanities, arts, and sciences to connect. I had really meaningful conversations with the synthetic biology faculty. The science they do often trickles into the society realm, demanding social engagement. Any field that might simultaneously cure all genetic diseases while building pathways to bring animals like the wooly mammoth back from extinction or open the door to designing babies to have specific physical characteristics needs to broaden how it thinks about ethical responsibility. Just a few years ago, we didn’t know we would need to ask these sorts of questions. Sometimes the dynamics of the lab aren’t suitable to voice, explore or answer these questions.

I’m always arguing that arts and sciences appear to be different, but we share a core belief that we want to increase the sensitivity of our observations. What does it mean for a poet to be sensitive versus for a particle accelerator to be sensitive? Both help us understand the world in a deeper way. Both want to reveal the intricacies of life. We become more empathetic beings in the process.