The Nexus and Understanding Different Ways of Thinking

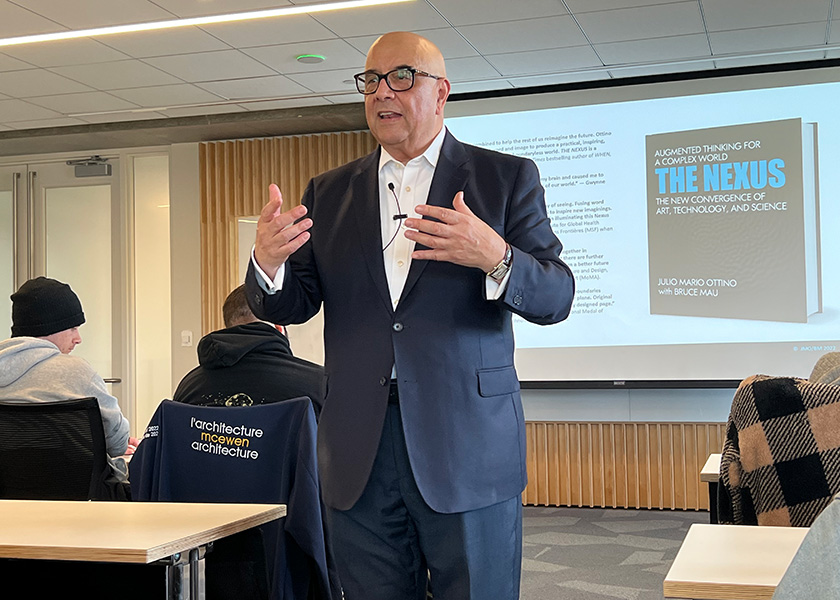

Dean Julio M. Ottino and Bruce Mau shared insights from their recent book

From pandemics to climate change, the world’s problems are more complex than ever. To devise solutions to these challenges, there must be new ways of thinking that combine art, technology, and science to expand our creativity and augment our insight.

That creativity, however, must be combined with the ability to execute. During their October 20 talk, “The Nexus: The Concepts, Its Design, and Implications,” based on their book, Northwestern Engineering Dean Julio M. Ottino and Bruce Mau explored how leaders can understand and manage those complexities.

“The Nexus thinking, what we’re advocating here, is augmenting your thinking space by drawing from both sides [of your brain] at the same time,” Ottino said, referencing left-brain rational thinking and right-brain creative thinking. “The point of the book [is] if we can convince people to understand how other people think, and not equate them with the end products of what they produce, then we have reached one of our objectives.”

A distinguished fellow in the Segal Design Institute, Mau is a designer, artist, entrepreneur, author, and educator. He has designed and coauthored books with, among others, Rem Koolhaas (S,M,L,XL). For many years, he designed all of the books published by Zone Books, the Getty Research Institute, and the Gagosian Gallery.

“Design is a methodology of not knowing,” Mau said. “Practically, nothing that I’ve ever done I knew how to do. People ask us to work on problems that haven’t been solved. We’re really starting from not knowing, questioning, exploring, and you have to get a kind of comfort with that ‘not knowing’ state of mind, state of being.”

“You have a methodology that you do know, so you have a process and a methodology that you do know, and you know it will eventually bring you through that valley of not knowing.”

Ottino and Mau shared insights from their book, The Nexus: Augmented Thinking for a Complex World – The New Convergence of Art, Technology, and Science, (MIT Press, 2022) and how its lessons can be applied.

Below are three takeaways from their talk.

Seeing simplicity and complexity

Bulls were a prominent part of Pablo Picasso’s art. From December 1945 to January 1946, Picasso produced 11 lithographs of the animal. He strived for realism with his first three attempts before taking an increasingly abstract approach for the last eight sketches. The final lithograph was just an outline, stripping the art of detail but maintaining the essence of the bull.

There’s a lesson that applies to Nexus thinking. The full bull represents complexity, and Picasso went from complex to simple. When it comes to many problems, one wants to go from the kernel of the idea to understanding the complications ahead, which many struggle to do.

“There are people who are good at doing one, but not the other one,” Ottino said. “You have to train yourself to be good at both and you have to be able to see simplicity in complexity, complexity in simplicity, and sometimes both at the same time.”

May the force (of Nexus thinking) be with you

Filmmaker George Lucas’s impact on society has been immense. The creator of Star Wars, Lucas’s work has spawned franchises, businesses, and even cultures. For just one of countless examples, Pixar was originally part of Lucasfilm and produced megahits such as “Toy Story” and “Finding Nemo.”

Lucas, Mau argued, is a Nexus thinker who was able to mesh art, technology, and science better than almost anybody over the last half-century and produced an “extraordinary” body of work.

Recently in Los Angeles, construction began on the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art. The museum synthesizes art, science, and technology which symbolizes how Lucas thinks.

“It’s proof of the potential of this way of working and what happens when you bring teams together,” Mau said. “Not only was he himself a Nexus thinker, but he was masterful at bringing Nexus teams together to do projects across those [fields].”

Knowing context is important

Thomas Harriot and Galileo Galilei were brilliant thinkers with similar interests. In 1609, London-based Harriot became the first person to make a drawing of the moon using a telescope. A few months later, Galileo did the same from Florence, Italy, with slightly upgraded tools.

While their interests and technology were similar, the end products of their work looked radically different. Harriot’s ink drawing lacked detail, whereas Galileo accurately depicted the moon’s craters and contours in watercolors and proved the celestial body was not a smooth sphere.

So, what accounted for that disparity even though both saw the same thing?

Harriot was an astronomer; Galileo was a physicist— but also an artist trained in Florence. He was admitted to Florence’s Accademia delle Arti del Disegno, and practically anybody who was an artist in that area during that time underwent exercises in the use of light and perspective.

“Why did [Galileo] go further? Because he was in Florence,” Ottino said. “In Florence, that was in the air, this intersection between art, technology, and science and the importance of the environment.”