McCormick Students Develop Devices for Visually Impaired

Specialized treadmill, safety pins, among devices developed by freshmen in Design Thinking and Communication course

Since developing diabetic retinopathy and losing her sight more than 30 years ago, Beth Finke has had to find new ways to do everything from cook to read.

A seeing-eye dog helps her get around on her own, but the pairing elicits a fair share of stares, and “as long as (people) are watching, I want to look good,” she says. That means finding clothes that match – difficult when she can’t see or remember which shirt is which color.

Enter freshmen students in McCormick’s Design Thinking and Communication course, who tackle problems like these for people living with disabilities. Over winter quarter, two sections of the class found myriad, elegant solutions to help the visually impaired live and thrive.

The course, required of all McCormick students and co-taught by faculty from Northwestern’s Writing Program, places students in teams and charges them with a problem. Students must observe the user, brainstorm, create prototypes of their ideas, and ultimately communicate their ideas back to their clients.

Over winter quarter, one section of the class worked on solutions for identifying Finke’s clothes, while another section developed systems to inform blind runners of their time, distance, and speed on a treadmill.

Finding clothes that match

Before the course, Finke developed her own system of identifying the colors of her clothes: she pinned safety pins on the tags of black clothes and pinned paper clips on white clothes. She tried to identify colored clothing by memorizing how each piece felt.

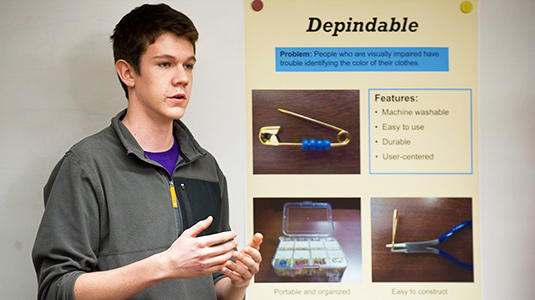

The solution was so elegant that students in the course decided to expand on it. One team developed a safety-pin bead system – the number of beads on the pin corresponded with the color of the clothing – while other teams developed different shapes to pin onto different colored clothing. One team, which called their creation Fantagstic, developed pinnable acrylic shapes that tell the user the clothing item’s color group – warm, cool, or neutral – as well its shade (dark or light).

The solution was so elegant that students in the course decided to expand on it. One team developed a safety-pin bead system – the number of beads on the pin corresponded with the color of the clothing – while other teams developed different shapes to pin onto different colored clothing. One team, which called their creation Fantagstic, developed pinnable acrylic shapes that tell the user the clothing item’s color group – warm, cool, or neutral – as well its shade (dark or light).

“We feel it will immensely expand her wardrobe,” said student Connor Donovan. “It empowers the user.”

Another team even developed an entire organizational system – pinnable tags, corresponding closet dividers, and customized clothing hampers for different groups of colors.

“We think it will increase the general organization of Beth’s life,” said student Monica Peppel.

That kind of design – one that goes beyond the immediate problem – was what made the students’ projects so strong, said Paul Olczak, an adjunct lecturer for the course.

“The students developed the right designs only after considering Beth's needs, the way the design would fit in her daily life, and the hidden complexities of identifying clothing without sight,” he said.

Finke herself was impressed with the designs and said it was a privilege to work with “talented and thoughtful young people.”

"What a great program,” she said. “These kids are just freshmen, and not only have they learned about design process, but also how much it can mean to work together to help people with unusual and unmet needs. I am already benefitting from all the ways they came up with to tag my clothes.”

Giving runners the information they need

Students in another section of DTC tackled a problem of a different sort: How could visually impaired runners know the statistics that a treadmill provides only visually: time, distance, and speed?

To find solutions, students spent time down at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, interviewing runners and testing prototypes. A device had to include an audio output, and it couldn’t have any loose wires that could trip-up runners. It had to include a button that the runner could push to receive the information, and it had to be easy for the user to feel while running.

Teams took two different approaches: plugging a device directly into the treadmill’s CSAFE (Communications Specification for Fitness Equipment) port, which connects to the treadmill’s microcomputer and allows the device to gather the information electronically, and using a wheel that attaches to the treadmill’s track and measures the information with a sensor.

For the team that developed the Click Trainer, a device that plugged into the CSAFE port and gave users information through a big button that gave a loud click when pressed, using the treadmill’s built-in electronic system was the best, most nonintrusive way to measure speed and distance.

“A lot of us were daunted by making an electrical device,” said student Jovanka Ravix. “But we combined all of our skills, and it ended up working out.”

But for the team that created Stat Track, a wheel-based system, using the CSAFE port wasn’t feasible, since treadmills manufactured before 2003 don’t have the port. Instead they developed a wheel that, when placed on the belt, uses a magnetic sensor to read the rotations. Their device then translates that information into time, speed, distance, and incline.

It involved several iterations of designs: How could they best mount it to the treadmill? How could they provide it with power? They eventually settled on a side-clamp and four AA batteries.

“Now it’s easy to put on and lasts for five hours,” said student Greg Chan.

In both instances, teams had to program their devices to translate information from the treadmill into a voice that would speak to the runner through headphones. (In some cases, the voice was computerized; in others, it was a team member’s recorded voice).

“I was very impressed with the dedication and drive of the students,” said instructor Kayla Matheus. “I think the students were motivated by their visits to RIC and interacting with the user in person. Not only did it inform their designs, but it inspired them to work harder on their projects and deliver a sound final product.”

“I was very impressed with the dedication and drive of the students,” said instructor Kayla Matheus. “I think the students were motivated by their visits to RIC and interacting with the user in person. Not only did it inform their designs, but it inspired them to work harder on their projects and deliver a sound final product.”

“I like designing and building things, so this was big for me,” said student Yjaden Wood, who worked on the Click Trainer. “But the project also taught us how to design posters, think about aesthetics – things I haven’t learned before. That was my favorite part.”

Learning that aspect of human-centered design is a big part of the course, said Lisa Del Torto, lecturer in the Writing Program and co-instructor of the class.

“Communication is at the core of every bit of this project, with a design problem and solutions that are based on how users and treadmills can communicate effectively for the users' purposes,” she said.

The Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago even plans to implement one of the students’ designs at their facility.

“The students did an incredible job creating some very plausible solutions,” said Eric Johnson, a Rehabilitation Institute program specialist who worked with the students on the project. “We strive to make our fitness center at RIC as accessible as possible, and these devices would make a huge impact fulfilling that vision.”