You're Never Too Old to Rock and Roll

Engineering thinking helped Thomas Tyrrell shape artists' contract negotiations and intellectual property issues in the music industry.

Thomas Tyrrell (’67) always loved music. As a Northwestern Engineering student, he quickly fell into the 1960s music subculture on campus. Every Friday afternoon, he and his friends went to Chicago, first combing through the vinyl at Rose Records, then taking in a classical music concert at Orchestra Hall.

Thomas Tyrrell (’67) always loved music. As a Northwestern Engineering student, he quickly fell into the 1960s music subculture on campus. Every Friday afternoon, he and his friends went to Chicago, first combing through the vinyl at Rose Records, then taking in a classical music concert at Orchestra Hall.

He and seven roommates were even evicted during winter finals for playing music in their off-campus apartment. “We got into a thing with the owner downstairs that we shouldn’t play our records so loud,” he says. “My roommate was a bit of a hothead, so that night he put the stereo on the floor with the speakers face down and played the 1812 Overture. When we came back from class the next day, we had our eviction notice.”

Quickly, Tyrrell moved to Sargent Hall. He has a prescient photo of himself there listening to his latest purchase—the CBS/Columbia Records LP of Pablo Casals and the Marlboro Festival Orchestra’s Six Brandenburg Concerti of Johann Sebastian Bach. “Little did I know that I would spend most of my career at CBS Records and its successor, Sony Music,” he says.

After more than 30 years in the music industry, the now-retired general counsel for CBS Records and Sony Music and executive vice president of Sony Music International looks back over an exciting career spent negotiating artist contracts for superstars like the Rolling Stones, Freddie Mercury, Michael Jackson, Leonard Cohen, Vladimir Horowitz, and Julio Iglesias. And he supervised a network of international music companies to help lead the industry’s fight to stop the nearly fatal attack of Internet digital piracy.

Ready for Anything

Things change fast in the music business. Thankfully, Tyrrell says, Northwestern taught him how to think on his feet.

“We learned how to search for practical, workable solutions in changing situations of uncertainty and complexity,” says the former Industrial Engineering and Management Sciences Advisory Board member. “You’ve got to keep an open mind and be ready for anything.”

That flexibility helped Tyrrell transition to New York University’s School of Law. Although he grew up in Calumet City, Illinois, he felt at home in New York, where he has lived ever since. “I had my first pastrami sandwich and said, ‘Where has this been all my life?’” he laughs. “From that moment, I was a New Yorker.”

He spent three years as a litigator on Wall Street, but everything changed at a farewell lunch when he learned his colleague was moving to RCA Records’ law department. “A light went on— I never thought you could work for a record company,” he says. “I told him to give me a call when something opened up. He did, and that was the rest of my career.”

"We learned how to search for practical, workable solutions in changing situations of uncertainty and complexity. You've got to keep an open mind and be ready for anything."

In 1974, Tyrrell began work as a contract specialist in RCA’s law department. Soon, he was working on contracts for young artists about his age—David Bowie, John Denver, Lou Reed, and Jefferson Starship. But, in 1977, he read in Billboard that RCA was moving the department he worked closely with to Los Angeles. Not wanting to leave New York City, he sent his resume out immediately. “Within a couple of months, I was working at CBS Records in New York,” he says. “I knew the business, and they were able to just drop me on big contracts immediately.”

Never Starstruck

The first big deal Tyrrell worked on at CBS was with Spanish singer Julio Iglesias, now considered the world’s most commercially successful Latin artist.

One of Tyrrell’s funniest memories happened at a reception for Iglesias during the peak of his fame. As Tyrrell talked with the singer’s manager, they couldn’t find Iglesias anywhere. Then they spotted him in a corner chatting with Tyrrell’s wife, Lani. On the way home, Tyrrell asked her about the conversation. Lani said Iglesias told her, “When you go to bed with your husband tonight, whisper in his ear, ‘Julio wants more money,’” Tyrrell laughs.

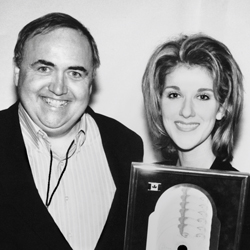

Never starstruck, Tyrrell focused on the deals. Still, he has many fond memories of artists, including negotiating the first Englishlanguage contract for teenager Celine Dion.

Once, when Dion was in New York to launch an international tour, he escorted her to an industry dinner in a limo with his daughter. “Celine gave her an autographed photo that said, ‘Elly, good luck next year in high school!’ Well, Elly is 40 now, works as a lawyer in New York, and still has that photo.”

A Cautionary Tale

Tyrrell loved his work, but it wasn’t always fun. He faced a huge challenge in 1982 when Sony Corporation convinced CBS Records to switch from records and cassette tapes to compact discs. At the time, CD players were priced at $1,000, and factories and record stores were configured to the older formats. The daunting problem became Tyrrell’s to solve globally.

“You can’t push a button and next Monday everybody goes to CDs,” he says. “So, we started in the United States and rolled it out one step at a time.”

It took nearly 10 years before CDs outsold vinyl records and cassettes. Sony Music ended up buying CBS Records, where Tyrrell spent the rest of his career.

The transition to CDs tells a cautionary tale. When CBS executives considered the switch, concerns that CDs could be copied were brushed off, thinking the technology was too expensive to tempt music pirates. But technology evolved, and duplicating CDs became easy. “We did not anticipate the Internet, and we certainly didn’t anticipate the delivery of albums over the Internet,” Tyrrell says.

Soon pirated digital copies of Sony’s albums appeared on filesharing platforms like Napster, Grokster, and LimeWire. Tyrrell testified at multiple Congressional hearings. “The Congressional committee members said we were burying our heads in the sand and asking the government to protect us,” he remembers. “I said to them, ‘We’re talking about a delivery system that is all the music you want, anytime you want it, for free. How do we compete with free?’”

A Different Business

During the next several years, numerous music-industry lawsuits against illegal file-sharing companies proved successful in essentially killing most pirating companies. Over time, the industry developed legal subscription services and other digital platforms, now the major methods for selling and distributing music.

Today’s music business is much different than the one Tyrrell remembers. He mourns the loss of record stores he haunted as a student. Still, he had a great time working in the industry he loved.

Now 14 years retired, the Northwestern Alumni Merit Award winner says he was fortunate to be there. “There were Sunday nights I would have paid money to come in Monday morning to find out what was going to happen next.”