Research Shows Cuba’s Internet Issues

Configuration issue makes traffic slower traveling back to the island

In December 2014, President Barack Obama made history by reestablishing diplomatic relations with Cuba, which included loosening its economic embargos. Two months later, American companies like Netflix and Airbnb announced plans to expand into the once-banned island.

“Our first reaction was: ‘Really?’” said Northwestern Engineering’s Fabián E. Bustamante. “As a business model, Netflix and Airbnb rely on most people having Internet access. That’s not quite the case in Cuba, so it really didn’t seem to make much sense.”

“Our first reaction was: ‘Really?’” said Northwestern Engineering’s Fabián E. Bustamante. “As a business model, Netflix and Airbnb rely on most people having Internet access. That’s not quite the case in Cuba, so it really didn’t seem to make much sense.”

Wanting to see if these business ideas were feasible, Bustamante, professor of electrical engineering and computer science in the McCormick School of Engineering, and his graduate student Zachary Bischof decided to measure Cuba’s Internet performance. They found that Cuba’s Internet connection to the rest of the world was perhaps even worse than they expected.

Bischof will present their findings on October 30 at the Association for Computing Machinery’s 2015 Internet Measurement Conference in Tokyo.

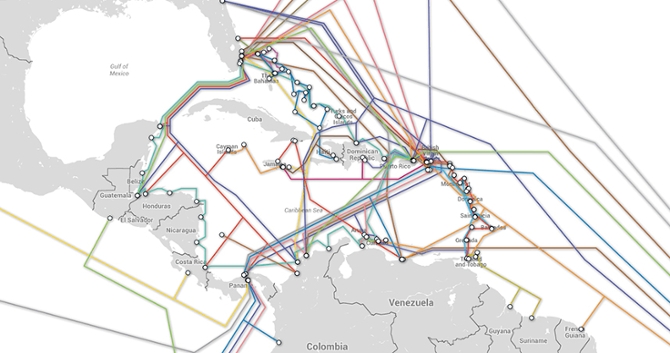

Cuba’s history with computing and Internet is a complicated one. Its citizens were not even allowed to own a personal computer until 2008. In February 2011, Cuba completed its first undersea fiber-optic cable with a landing in Venezuela, but the cable was not even activated until two years later. Today, about 25 percent of the population is able to get online and just five percent of the population has home Internet.

“If you’re trying to connect anywhere, you either have to connect through these marine cables or up to the satellite,” Bustamante said. “If you go up to the satellite, it would take significantly longer.”

“For one, it’s much farther to travel,” Bischof added. “And the trip is on a very interference-rich environment, which include cosmic rays.”

Since March 2015, Bustamante and Bischof have been conducting measurements from a server in Havana to observe Internet traffic going in and out of Cuba. They measure the amount of time it took for information to travel in both directions, taking note of the paths of travel. In early results, the team found that information returning to Cuba took a much longer route.

During their study, Bustamante and Bischof found that when a person in Havana searched for a topic on Google, for example, the request traveled through the marine cable to Venezuela, then through another marine cable to the United States, and finally landed at a Google server in Dallas, Texas. When the search results traveled back, it went to Miami, Florida, up to the satellite, and then back to Cuba. While the information out of Cuba took 60-70 milliseconds, it took a whopping 270 milliseconds to travel back.

“It takes so long that it’s almost useless,” Bustamante said. “You can start loading a webpage, go have coffee, then come back and maybe you’ll find it.”

Bustamante and Bischof said this could be the result of a configuration problem or routing policy and are currently exploring this further. For now, they can only say — with certainty — that Cuba’s Internet performance appears to be among the poorest in the Americas, and its infrastructure would struggle to support web services hosted off the island, particularly network-intensive applications like Netflix. Understanding the problems and diagnosing their causes will help Bustamante, Bischof, and other teams propose future solutions.

“Beyond Internet services like Netflix, to continue societal progress in Cuba depends on better connectivity,” Bustamante said. “To better understand how to improve it, we first have to better understand what is available now.”