Starting Your Startup: Professors Discuss Methods for Getting Up and Running

Chad Mirkin and Milan Mrksich present the final Farley Fellows entrepreneurship seminar of fall quarter

When Northwestern University nanotechnology expert Chad Mirkin set out to launch his first startup in 1998, he had little idea what he was getting into.

“I had no experience and no idea how to commercialize anything,” he said, addressing a standing-room-only group of Northwestern students on November 12. “You guys are lucky to have an infrastructure.”

Fifteen years ago, few programs existed at Northwestern — or other universities — to help faculty and students bring their technologies to market. But since the 2007 advent of the Farley Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Northwestern’s entrepreneurial culture has flourished.

“We have always had a few researchers who pursued startup companies, but they were the outliers,” said Julio M. Ottino, dean of Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science. “Since we have introduced programs to encourage entrepreneurial thinking, we have seen a flurry of ideas and activity, both across the University and especially at McCormick.”

“We have always had a few researchers who pursued startup companies, but they were the outliers,” said Julio M. Ottino, dean of Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science. “Since we have introduced programs to encourage entrepreneurial thinking, we have seen a flurry of ideas and activity, both across the University and especially at McCormick.”

Today’s resources include the Farley Center, offering incubator space, pre-seed funds, and guidance for faculty and student startups; Northwestern’s Innovation and New Ventures Office (INVO), which manages invention disclosure, assessment, and patenting for technologies; and courses like NUvention, a popular slate of interdisciplinary entrepreneurship courses in which students launch startups in a variety of fields.

This fall, a new McCormick lecture series advanced the entrepreneurship conversation: the Farley Fellows Seminar Series. The talks invited entrepreneurship-minded faculty members to share their vast knowledge and advice with students and fellow faculty.

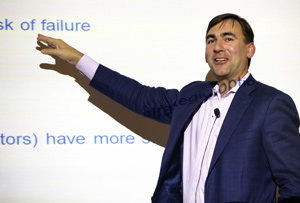

The final talk of fall quarter featured a discussion of various startup models with Mirkin, George B. Rathmann Professor of Chemistry, Chemical and Biological Engineering, Biomedical Engineering, Materials Science and Engineering, and Medicine; and Milan Mrksich, Henry Wade Rodgers Professor in Biomedical Engineering, Chemistry, and Cell and Molecular Biology.

Mirkin shared advice gleaned from his work co-founding four startups, including Nanosphere Inc., a diagnostic equipment maker that uses nanotechnology principles to test for medical conditions, and AuraSense Therapeutics, a biotechnology company that commercializes spherical nucleic acid (SNA™) constructs as gene regulation and modulation agents for diseases.

The two companies evolved through very different models, Mirkin explained: while Nanosphere grew through the support of venture capitalists and other investors, AuraSense partnered with a large pharmaceutical company.

Growing with the support of an established company reduced the co-founders’ potential earnings, but it also mitigated financial risk and reduced the pressure that comes with accepting investor dollars.

“We didn’t have the aggressiveness of a lot of the (venture capitalists),” Mirkin said. “When you take an investment, the train leaves the station, and it will continue on with or without you.”

Whichever strategy an entrepreneur chooses, he or she must create a careful plan with achievable goals, establish an intellectual property position, assemble a team with technical and business experience, and have in mind an “end-game,” Mirkin said.

Whichever strategy an entrepreneur chooses, he or she must create a careful plan with achievable goals, establish an intellectual property position, assemble a team with technical and business experience, and have in mind an “end-game,” Mirkin said.

Mrksich followed a different path to start SAMDI Tech, a provider of fast, high-quantity assay services (processes that test for enzyme activity) for drug discovery. He leveraged his position as a university professor to commercialize his discoveries, a process he calls the “slide-into-start” or “internal start” model.

When Mrksich decided his technology was “ready for prime time,” he considered the resources in his research lab. He had talented researchers skilled at proposal-writing, specialized equipment, and a network of peers and alumni to serve as partners and potential clients. Without these academic ties, building a startup would have been far more difficult and costly, Mrksich said.

“It’s not easy the first time, because you don’t have the contacts, you don’t have the reputation,” he said. “A small company doesn’t even have a library. Do you know how expensive it is to buy an article without a library?”

There are other considerations, Mrksich said. For example, when researchers spin out a company from a university lab, the university becomes a shareholder, but they are typically passive and their holdings are modest, often under 10 percent.

“They’re the best investor you could have,” Mirkin said.

Read about Ed Colgate and David Mahvi's Farley Fellows talks.

Read about Greg Olson and Michael Peshkin's Farley Fellows talks.